The Last Harvest: The Mass Extinction of Rural Farmers, Hyperinflation, and Regional Economic Collapse [DRAFT]

The fate when innumerable trends converge

(~43 minute read… so far)

Author’s Note: This is an ongoing research piece that I am actively working on. After discussing briefly with some close friends and colleagues within the industry, there was a collective encouragement to urgently share. What follows is a draft version I began writing today (2/3/25) covering the first four sections. I have noticed some trends pickup pace the past ~5 years while working at the cross-section of these various fields. This first draft is from the notes that just two months ago I began jotting down out of personal interest to explore further at some point.

I would have liked to spend much more time researching more deeply into these topics before releasing anything, but at the request of those who will be directly impacted, the stakes felt too high to not get a dialogue started. Because of that, I will be strictly focused on just getting the content out as quickly as possible (so please excuse what I assume are many typos currently). I will then come back to add sources and references as quickly as I can. If you have thoughts, insights, or firsthand experiences related to this topic, I encourage you to share them—your input could help shape the final version, and would be greatly appreciated for the research I still plan to complete.

EDIT: When I wrote and released the draft on February 3rd, I originally posted, "Tomorrow I will write the 5 remaining sections from current notes". Clearly that was optimistic as I've spent the past few days diving into further research of Section 5 alone. I initially planned to share the various small and medium-sized issues that I've experienced adding up. I've realized this section needs to go deep rather than broad though, and be incredibly insightful rather than light touch. The truth is that every word is intentional, serves a purpose, and is necessary because of the gravity of the situation. Unlike I'd hoped above, it does require some additional research until I feel confident in the claims. I will be releasing the remaining pieces iteratively.

Change Log

(This article is a work in progress. Below is a record of updates and revisions.)

🆕February 10-11, 2025: If anyone has been checking back on this the past couple of days, I apologize there has been no progress. I got some unexpected and unsettling health news that I had to take care of. I will be back on this asap.

---February 9, 2025

Section 5: I'm still expanding on Section 5. Even narrowing down to a single resource, water, opens what seems like a never-ending stream of issue after issue. I can't lie. It's depressing at this point. I thought I had a good grasp of the overarching issues, but the deeper you dig the more there is. I'm asking myself, "When do I stop?", but also in my head is, "What's the point of all this?". I get it with how that sounds very melodramatic. But if there is this much damning information and instead of pressing the big red emergency stop button, the accelerator is getting pushed to the floor from every angle... damn. How are we not doing better than this as humans?

Introduction

For over a decade, I’ve navigated the intersection of technology, startups, and economic development, which has given me a unique vantage point across the entire agricultural spectrum—from the small-family to industrial farms, local dealers to multinational corporations, agtech startups to 70+ year-old established ag equipment manufacturers, agriculture analytics companies to university research labs, angel investors to rural banks to private equity firms, and city to state and federal government agencies.

I haven't just talked to them. I've helped build multiple hardware and software applications to solve their problems, developed programs to further research, raised public and private dollars to support initiatives, and had a beer or two in their shops and at local breweries. This cross-sector exposure has revealed an alarming convergence of factors that threaten the survival of rural farms, setting off a chain reaction that extends far beyond the fields.

The unordinary, much-worse-than-before massive worker shortage that will happen this year, acceleration of corporate consolidation, major uncertainties and confusion with shifting economic policies, and supply chain disruptions are not only difficult on small farms, rural communities, and regions that depend on them, we will see the largest loss in the number of farms in the history of the United States in 2025. This mass extinction event is a the catalyst that kicks off multiple rapid feedback loops, both human-made and natural climate. This cause will effect job losses like we’ve never seen before (this is not specific to the agricultural industry), hyperinflation on products that all come from the agriculture industry, and will drive entire rural communities and regions into further economic and social depressions—if not complete ruin. If you don’t believe any of this, maybe you will consider that this isn’t the first time we’ve been in this situation before (More on that in Section 3)—but this time the stakes are even higher.

This is not just a crisis for farmers—it is a crisis for the entire nation. If we fail to address these forces now, we risk an irreversible collapse of many more rural economies, our nation's food abundance and security, and regional micropolitan stability that are adjacent to these places. This research piece will discuss the underlying mechanisms fueling this mass extinction of independent farms and examine the broader consequences that are rippling through society. The question we must ask: Can we act before it’s too late?

I was born and raised in Sikeston, Missouri, a town of just 16,000 people where on the outskirts, acres of cropland stretched endlessly beyond two-lane highways and two interstates. Two blocks from the neighborhood where I grew up, one of the town’s busiest intersections—though “busy” is relative in a place like this—was anchored by a local bank, a family-owned nursery, and a gun shop. Right next to them? Corn and cotton fields. In a town like Sikeston, farmland wasn’t just something you passed by on the way to school or the grocery store—it was woven into daily life. I was born in 1988 and still then, a lot of my close friends' families were farmers. It wasn’t unusual to find crops growing on a five-acre plot tucked between that bank and the Domino’s Pizza.

I never farmed. My path led me into tech, then startups, and eventually into economic development. Cue the rural stereotypes though—within the past decade I have had opportunities to work in the agtech space, an industry that sits at the crossroads of innovation and agriculture. That journey has allowed me to work alongside some of the most hardworking, brilliant, and talented people I’ve ever met. But more importantly, it has given me a rare perspective—one that connects the realities of small towns, rural communities, and the regions that surround them with the high-level decisions shaping their futures. I haven’t just seen what’s happening to America’s farms; I’m living in it. I've seen the larger forces at play, the systems quietly being rewritten, and the unspoken consequences waiting on the horizon.

1. Labor Market and Demographic Realities

1.1. Aging Farmers and a Looming Succession Crisis

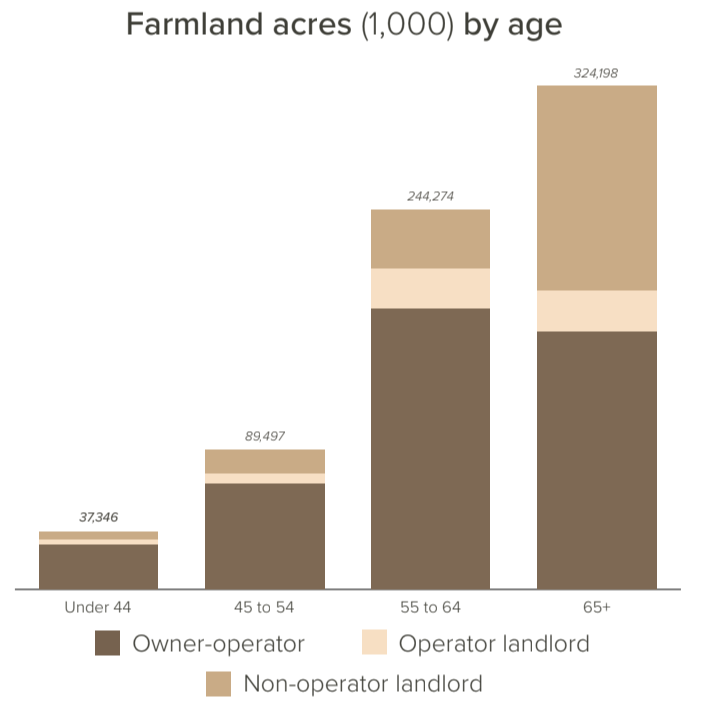

Generational family-farms are becoming a thing of the past and we're at a tipping point. Nearly 96% of farms are small family-owned. The group of farmers who are over the age of 55 makeup 63% of U.S. operators who own over 80% of cropland. The family succession statistics are stark: only 30% of family farms transition successfully from the first to the second generation, 10% survive to the third, and less than 4% make it to the fourth. The slow-motion collapse of farm succession is not just a family tragedy—it’s a systemic unraveling of rural America. Every farm that fails to transition is either abandoned altogether and sold to be repurposed as residential or commercial space, or absorbed by large industrial farms or corporate interests, accelerating the decline of independent agriculture.

1.2. A Disappearing Workforce

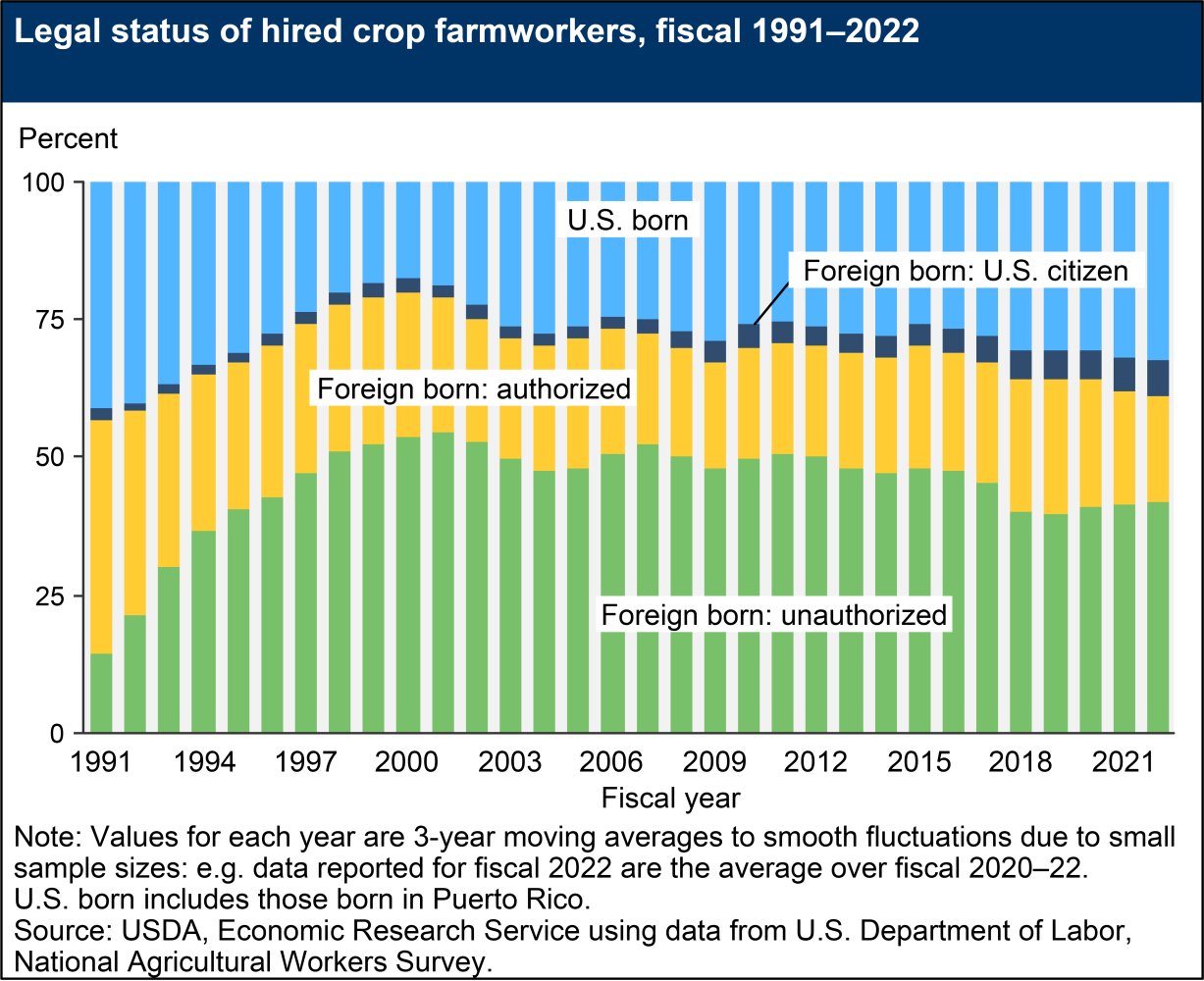

It’s no wonder the succession percentages are so low though—nearly always cited as the #1 or 2 issues facing farmers are labor challenges. Agriculture in the U.S. has long been reliant on immigrant workers who make up nearly 70% of the agricultural workforce (an estimated 40% are undocumented). Specifically for farms that focus on agricultural crops, 50% of their workforce are seasonal migrants. The H-2A program is designed to fill these seasonal labor gaps. The number of certified H-2A workers increased by 65% from 225,000 to 370,000 between 2017 and 2022, yet it remains a contentious policy battleground. At best, left-leaning policy aims to increase regulation and slow the efficiency of the program while at worst some right-leaning initiatives aim to eliminate the program altogether. These moves could cripple farms dependent on timely, seasonal help, increasing the likelihood of crop losses and financial strain.

As policy shifts through the labor market, the on-the-ground effects are stark. With the recent tightening of immigration enforcement and rising deportation numbers, some farms have reported a majority of their crews simply not showing up at the beginning of this year, leaving crops unharvested and operations in limbo. The consequences of these abrupt policy shifts are going to be felt immediately and severely—lost yields, financial instability, and a workforce that is soon-to-be nowhere to be found. Each missing worker is another thread pulled from the fabric of America’s agricultural backbone.

1.3. Rural Collapse: A First Domino

As labor shortages intensify and farm succession fails at an alarming rate, American agriculture stands at a critical crossroads. This labor and demographic crisis is not occurring in isolation–as we examine the forces driving these changes, it becomes clear that labor and demographic realities are just the beginning. Looming over these challenges are broader economic currents, policy decisions, and market forces that threaten to reshape the very foundation of the nation’s food system. Understanding these domestic economic pressures will be essential to grasping the full scope of what’s at stake.

2. Economic and Consolidation Pressures

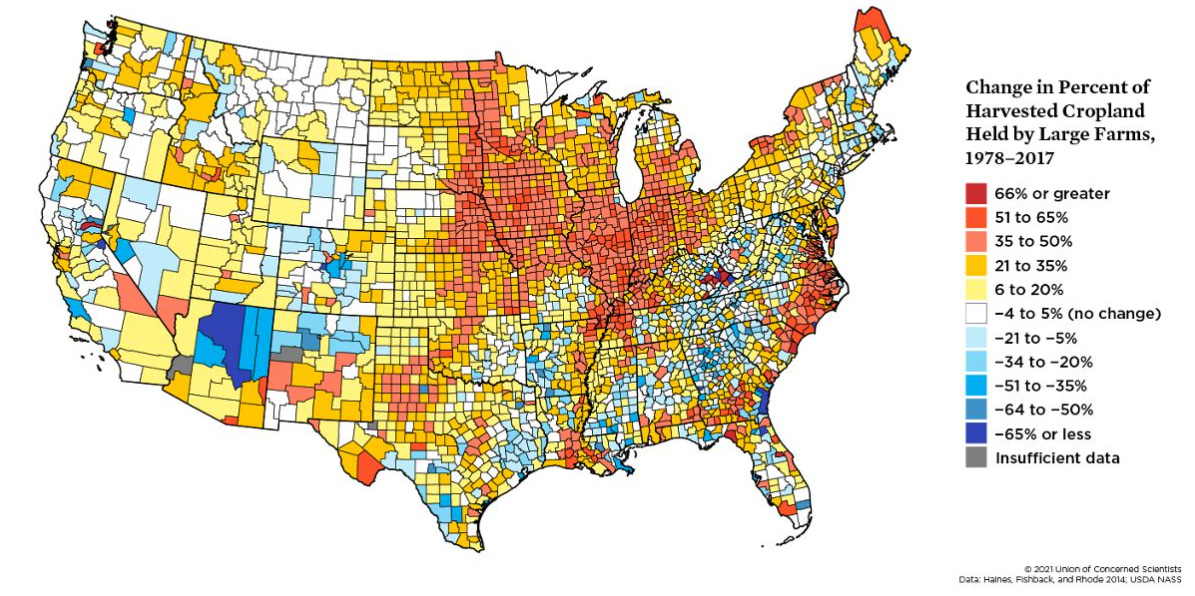

2.1. The Growing Consolidation

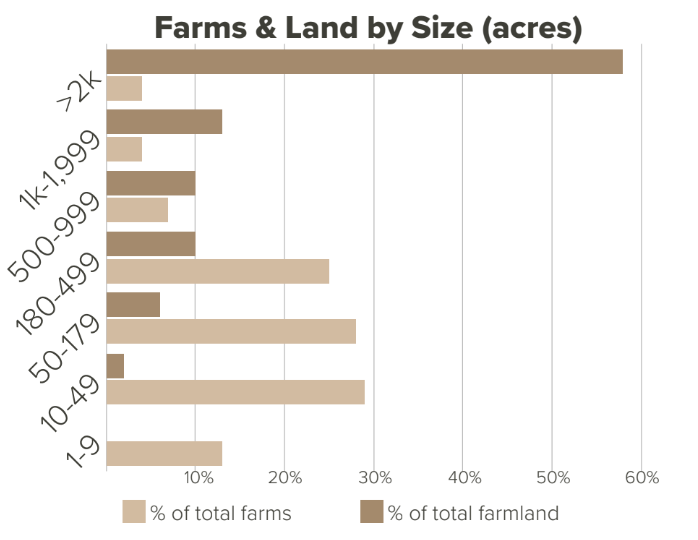

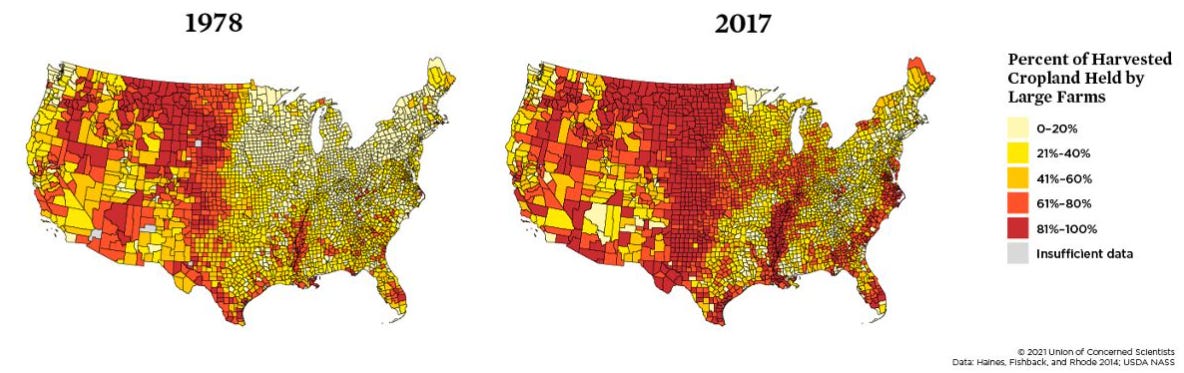

In just half a century, the U.S. has lost over an estimated 700,000 farms (142,000 of those between just 2017 and 2022), a decline that shows the sheer magnitude of consolidation in agriculture. According to the 2022 Census of Agriculture, the total number of farms in the U.S. has fallen below 2 million for the first time since before the Civil War.

The dominance of large farms–whose efficiencies, scale, and technological advancements have driven agricultural progress in many ways–is reflected in their own prosperity: despite accounting for less than 1% of all farms, they generate over 40% of total agricultural sales. This shift is not inherently a problem, but as we will examine in the final section, such extreme concentration of farmland and production doesn’t just bring efficiency–it brings fragility. As consolidation accelerates, it creates risks that don’t just grow in size–they multiply in speed and unpredictability. The moment a crisis hits, the fallout will be immediate, widespread, and largely irreversible. Past shocks have been in finance, the internet, oil, steel, coal, and manufacturing. What happens when the next one involves our food?

2.2. The Farm Bill: A Fragile Lifeline

Farmers don’t operate in a free market. Decades of government intervention, subsidies, and regulations have shaped the economic landscape of agriculture—sometimes offering stability and food security, but often creating unintended dependencies that now threaten to collapse. This becomes evident in the paradox of the 2018 Farm Bill, a $428 billion package meant to stabilize the industry after the economic shock caused by the 2018-2019 trade wars. With the Farm Bill set to expire in 2024, and only a temporary one-year extension in place, the industry is staring down a future where these artificial support structures may vanish overnight.

2.3. The Subsidy and Regulation Levers: From Safety Net to Noose

[2/7/2025 URGENT EDIT: Last week I posted an article within 12 hours of the administration's freeze on federal grants and loans. If you followed the news you know there was mass confusion. I took it down less than 2 hours after posting as a supposed clarification came out and it seemed the ramifications were not going to be as widespread as I had assumed.

I've recently come across stories that some of my assumptions were in fact correct, which includes the massive ripple effects this is going to have on our economy (ESPECIALLY FARMERS AND RURAL COMMUNITIES). Here is the post with a letter and links for you to easily contact your Congressmen and women.

---

Government subsidies haven’t just assisted struggling farmers—they’ve also created a price system that corporations have learned to exploit. Many of these subsidies are tied to water usage, conservation efforts, or precision agriculture adoption, which introduces a new set of immediate threats in an era of labor shortages and economic instability:

Fewer Workers, Fewer Compliance Capabilities – With labor shortages accelerating, farms will struggle to meet the operational requirements for critical subsidies. Failing to comply means losing out on financial support they may be depending on.

Technology Incentive Gaps – Some subsidies require farms to integrate precision agriculture technology to qualify. However, with economic instability, fewer are less to adopt new technologies. With fewer workers available to operate, maintain, or train others on these systems, farms may be unable to comply, effectively locking them out of programs that were meant to keep them competitive.

Artificial Pricing & Markets – By publicly tying subsidies to specific crop yields and market conditions, corporate conglomerates have gained an unfair advantage–ensuring that farmers receive just enough to survive, but not enough to grow or adapt. This cycle keeps independent farms trapped while giving large agribusinesses the leverage to dictate market prices. This is further exacerbated at the global level discussed in the Geopolitical & Global Market Considerations section below.

The irony is inescapable: subsidies and regulations meant to protect farmers are, in many ways, accelerating their extinction. Credit is due to agribusiness giants for increasing efficiency and innovation, but their expansion has come at the direct cost of small farms—and by extension, rural America.

2.4. The Local Economic Fallout: A Chain Reaction That Won’t Stop at Rural Towns

Beyond the direct impact on farms, these shifts will have ripple effects that will devastate rural communities at a speed and scale most people aren’t prepared for. Unlike industrial farms–where profits are often extracted and funneled into corporate expansion–family farm income largely stays within the local economy. This distinction is critical.

When a family farm disappears, local economies suffer. Equipment dealers, seed suppliers, rural banks, and service providers all rely on the local farm economy to survive.

Corporate consolidation means fewer dollars circulate locally. The shift toward industrial farming means that profits flow upward to national and multinational agribusinesses rather than remaining within regional economies.

The domino effect accelerates rural collapse. As farming communities shrink, schools close, hospitals struggle, businesses shutter, and families are forced to leave. Less local tax revenue decreases the capabilities to provide needed services and critical infrastructure. This all creates a feedback loop of economic and social erosion.

These aren’t abstract concerns. This was a slow-moving trend at first—but rapid acceleration is happening right now, and it’s reached critical mass. The convergence of an aging farm demographic, severe labor shortages, accelerated consolidation, regulatory uncertainty, and trade policy (discussed in section 4) is driving rural America toward an immediate and self-perpetuating economic downturn. The tipping point isn’t about to come up—we have already begun to free fall.

As consolidation increases, micropolitan areas that are tied to food and farm goods and services will experience reduced demand. The increased concentration moves business to vertical giants. Small farms support regional food hubs, farmers' markets, and local supply chains that support both rural and urban food processing and distribution jobs. Corporate farms prioritize large-scale contracts and bypass regional distributors in favor of centralized logistics networks. This is when the surrounding and support of crumbling rural communities begins to crack their neighboring regional micropolitan areas.

2.5. The Uncertainty of the Next Economic Wave: How Many Will Survive 2025?

From direct conversations with Midwest farmers, many already expect to lose money in 2025—and we just entered February. Input costs continue to skyrocket—from fertilizer to wages to equipment—while subsidies remain in limbo and market pricing remains volatile and unpredictable. Meanwhile, new trade wars loom, and government policies continue to introduce both lifelines and landmines.

The question isn’t whether farms will struggle. It’s whether enough of them will survive. And as we turn to the global forces shaping these domestic conditions, the picture only becomes more complex, more volatile, and more dangerous.

The domestic farm economy does not exist in a vacuum. Many of the economic pressures we see today are symptoms of larger global forces. Trade wars, foreign competition, multinational agribusiness strategies, and shifting geopolitics are placing American farmers–especially small, family-owned farmers in rural America–at an unprecedented disadvantage in the global food economy.

In the section Geopolitical & Global Market Considerations section, we examine how foreign markets, tariffs and retaliatory tariffs, corporate pricing strategies, and export policies have created an economic battlefield where American farmers are losing ground fast. But first, as the saying goes: “History may not repeat itself, but it sure rhymes.”

3. Industry Collapses & Historical Parallels

The collapse of American farming is not happening as some unique event—it follows the same economic patterns that have devastated entire industries before. From the Rust Belt’s manufacturing decline to the downfall of coal towns and the gutting of the U.S. steel industry, the cycle is unmistakable:

A Dominant Industry Anchors a Region’s Economy – Entire towns and communities depend on one sector for survival.

Economic Shifts Introduce New Pressures – Consolidation, labor displacement, automation, and government policy changes create instability.

Small Players Are Pushed Out First – Larger corporations adapt, while independent businesses and local enterprises collapse.

The Industry Falls, and the Local Economy Implodes – Jobs disappear, businesses shutter, migration accelerates, and the region never fully recovers.

We’ve seen this play out before. Now, it’s coming for American agriculture.

Manufacturing & The Rust Belt (1970s-Present) – Offshoring, automation, and corporate consolidation hollowed out the once-thriving industrial centers of the Midwest, leaving behind economic wastelands.

Coal Towns & Energy Shifts (1980s-Present) – Mechanization and policy changes wiped out coal jobs, devastating entire regions that depended on them.

The U.S. Steel Industry (1980s-Present) – Trade policies, foreign competition, and corporate restructuring dismantled the steel industry, gutting local economies.

In each case, the warning signs were there, but the collapse was still devastating. Agriculture is now standing at the same precipice. The difference? If farms disappear, it’s not just jobs and towns at stake—it’s food security, supply chains, and the survival of rural America itself.

4. Global Markets & Trade

4.1. Trade Wars & Tariffs: A History of Unintended Consequences

The 2018-2019 trade war with China serves as a reminder of how quickly global market disruptions can devastate American farmers. The U.S. imposed tariffs on Chinese imports, prompting China to retaliate by slashing its purchases of U.S. agricultural goods—particularly soybeans, corn, and pork commodities from U.S. farm exports.

The impact was immediate and severe. U.S. agricultural exports to China plummeted from $19.5 billion in 2017 to just $9.1 billion in 2018, pushing countless farmers into financial distress. The government rushed to enact the 2018 Farm Bill, an effort to provide relief, but the reality was that we saw the largest bankruptcy and decline in small-family farms in U.S. history.

Now, in 2025, a new wave of trade volatility is emerging, following a similar pattern.

4.2. The 2025 Trade Turmoil: Instability at a Critical Moment

Just last week, the U.S. announced new tariffs on Canada (25%), Mexico (25%), and China (10%), triggering concerns across the agricultural sector. Economists argue that, in theory, such measures could increase domestic demand for U.S. farm products, but as past trade wars have shown, retaliation is almost inevitable—and the consequences often outweigh the intended benefits.

The reaction began in less than two days, Canada immediately imposed a 25% retaliatory tariff on key U.S. goods. While the initial wave of tariffs didn’t directly target agriculture, they did impact many products that rely on farm commodities for production. To note, Canada is the world’s largest producer of potash, a key potassium-rich fertilizer—46% of which is exported to the U.S. Any disruption in this trade could directly drive up costs for American farmers.

Mexico, a top importer of U.S. corn and soybeans, similarly responded with a tariff and nontariff response in which an estimated 1.7 million jobs could be lost in the U.S. (mostly in the South and Midwest).

Fortunately, U.S., Canada, and Mexico rescinded their tariffs less than a week after implementing them. This constant policy whiplash leaves farmers in limbo, unable to plan for the season ahead. Unlike large multinational agribusinesses, which have diversified export channels and financial buffers, independent farms are hit hardest by unpredictable trade policies.

4.3. Export-Driven Domestic Scarcity: A New OPEC for Food?

As corporate consolidation intensifies, U.S. agriculture is beginning to mirror the behavior of another critical industry: energy. Just as OPEC nations manipulate oil supply to control global pricing, we are seeing the emergence of corporate-controlled food exports shaping the global agricultural market.

Fewer firms now dominate exports, meaning that global food markets are more sensitive than ever to corporate pricing decisions. These firms are incentivized to prioritize higher-profit export markets, creating a dangerous scenario: domestic food production can increase while domestic food prices also rise. This pattern is already familiar. Despite record oil and gas production, U.S. energy prices remained high throughout the early 2020s because corporations prioritized global sales over domestic supply. Agriculture will follow the same trajectory. I don't know about you, but we stopped having food fights in primary school. I can't imagine the domestic and global toll it will take on society when our food supply chains are weaponized.

If corporate agribusiness treats food as a global commodity first and a domestic necessity second, American consumers could find themselves in a paradox where they pay more for food that is grown within their own borders.

4.4. How Government Policies Distort the Market and Leave (especially small-family) Farmers Behind

Beyond trade wars, the U.S. government has a long history of directly interfering with agricultural markets—often with unintended consequences. In past decades, the federal government has forbidden the export of certain crops to foreign markets. The result? Domestic prices collapsed, forcing the government to introduce subsidies just to keep farmers afloat. Likewise, some EPA-banned agricultural chemicals and fertilizers (for the sake of our own health) are still legally sold by U.S. companies in foreign markets where regulations are weaker. This means that foreign farmers can access inputs that are illegal for American farms, allowing them to produce crops at lower costs and compete more aggressively in global markets. While the intent behind U.S. environmental and consumer protection regulations is justifiable, the double standard it creates puts domestic farmers at a significant disadvantage in price competitiveness.

Even more damning is how multinational agribusinesses manipulate pricing between domestic and foreign markets to their advantage. American agricultural corporations often sell inputs and equipment to foreign farmers at a fraction of the domestic price. For example, a product that may be charged at $35 per unit in the U.S. is easily sold for just $3 per unit in another country. This then allows foreign farms to undercut U.S. farms in the global marketplace, worsening the competitive disadvantage for American farmers. U.S. farmers are locked into competing in global commodity markets where their competitors have significantly lower cost structures. The very companies that profit off American agriculture are simultaneously giving foreign farms an edge over their U.S. counterparts.

4.5. They that Control the Land and Food

One of the biggest unknowns in this shifting landscape is what happens when small and mid-sized farms vanish. Large agribusinesses primarily operate within global commodity markets, while small-to-mid-sized farms play a crucial role in regional and domestic food supply chains. Historical parallels, industry consolidations and collapses that left regional economic holes gives us reason to believe this newly established domestic food supply will cause prices to rise for consumers. Considering you can't eat petroleum, I'm concerned previous parallels we have considered may be stark in comparison to the literal demand food has on our survival. Without competition from smaller producers, will corporate agribusinesses manipulate food prices the same way Big Oil has done with energy?

Without small farms helping self-sustain regional economies that can oftentimes be shielded from global shocks, what happens when they disappear and our agricultural industry becomes a global bargaining chip? The consequences extend beyond price volatility—they could reshape geopolitical alliances, destabilize supply chains, and introduce food insecurity risks to an extent the entire U.S. economy is not prepared for.

---

The most disturbing fact of all? Everything we've discussed prior to this is made up of people, places, systems, inputs, and outputs that as a society can have certainties about, predict and protect, and control for. As we will see in the next section, the agricultural industry is more vulnerable than ever to ecological constraints, and start to move further away to systems we can't control. We will then conclude with discussing how every single one of these trends have put us in multiple perilous states—paths that we no longer ask "if". It's just a matter of "when". And we have absolutely no tools to accurately predict the timing or magnitude that openly welcome the occurrences of events that are even outside the scope of black swans—radical uncertainty, unknowable rareness, and beyond the realm of any computational or probabilistic reasoning.

(Author’s Note: This section of the writeup is still a work-in-progress)

5. _____ologies & Resource Constraints

By now, if you haven't caught on, I've strictly been talking about agriculture crops because it's the part of the agriculture industry I'm most familiar with. Here is a fun stat: there are just as many cattle and dairy farms with just as much farmland as those who strictly grow crops. Well, I guess it's not really such a fun fact in this context.

When I was doing quick research to fact-check my notes before posting, I thought the 'Geopolitical' section was going to be the most cumbersome as it's the one I have the least experience with. No, the the tangled interactions of the variety of disciplines—agronomy, climatology, geology, hydrology—have endless and complex variables and data. There is no shortage of factors that impact farming—biodiversity, climate, inputs, land, and soil. Agriculture's diversity is difficult to fit neatly into one universal narrative. What affects a citrus farm in Florida is not the same as what threatens a corn field in Missouri.

I won’t drown you in climate models, overwhelm you with endless variables, or lose you in the weeds of resource management. Instead, I’ll focus on just one thing. One thing every farm depends on. One thing so essential, so universal, that its absence reduces every innovation, every adaptation, every ounce of human ingenuity to dust.

Water.

More than a necessity, water is the unshakable foundation of agriculture—the difference between abundance and ruin, between a harvest and a wasteland. Without it, no breakthrough in technology, no revolution in soil health, no climate strategy, however sophisticated, can keep food production alive. Water is the great limiter, the final threshold, the line we cannot afford to cross. And here’s why:

Water is finite and fading: Unlike the air that we breathe or sunlight that shines on our fields, freshwater is running out—consumed faster than nature can restore it.

Water is becoming lost beyond return: Soil can be replenished. Forests can regrow. But when an aquifer dries up or a water source turns toxic, it is gone forever.

Water adds an exponential factor: Water scarcity does not strike alone. It tightens the noose on every other crisis—droughts last longer, soil erodes faster, production costs spiral, and climate volatility turns unpredictable seasons into unmanageable disasters.

Water loss means inescapable collapse: Land can be managed. Crops can be engineered. Farming methods can evolve. But without water? None of it matters.

This crisis isn’t creeping toward us—it is here. The wells have dropped, the rivers have retreated, and when the last of it is gone, the fields won’t just wither. They will die. The earth won’t just go dry—it will turn against us.

The soil seeps. The cracks creep. The flow falters... fades... fails. Starved roots. Splintered earth. Silence.

No, this is not a distant catastrophe—it is a countdown. And when the clock strikes zero, the winds will carry away the remains of our remaining harvest.

5.1. Irrigation and its Origins

The first Agricultural Revolution for humanity began around 10,000 BCE. This is when we shifted from being hunter-gatherers to stationary farmers as we know them today. There was a second Agricultural Revolution that began around 300 years ago that involved rapid mechanization and increases in production. To date, the least amount of innovation or change in agriculture crop farming can be found in water management with irrigation. While not the only factors, geography and topology are what mostly influence the method of irrigation (as they also incorporate major factors such as climate, soil, and crop type). It's helpful to know the different irrigation types that distribute our water to crops and where that water is sourced.

Irrigation Types

Flood irrigation is one of the oldest irrigation methods (dating back to thousands of years). Natural waterways or large-scale canals are how the water is initially transported, thus the name. It is used in nearly half of irrigated farmland and consumes more than 60% of all agriculture water. It's also the least efficient method of transporting water at just 40-60% efficiency. There is a reason it's been a mainstay. The equipment used for this type of irrigation is the least expensive to install, operate, and maintain.

The other types of irrigation include sprinkler systems, center pivots, and drip irrigation—with each being increasingly more efficient but also more expensive per acre to utilize.

Water Sources

For agriculture, there are two major sources: surface water and groundwater. Surface water includes rivers, canals, and reservoirs (basically above ground). About 40% of agriculture uses this source. It's accessible, has better recharge potential, and is less energy-intensive—but it is also highly volatile and has the lowest efficiency rate at 40-70% while suffering from runoff and evaporation.

The other source, groundwater, is where 60% of agriculture extracts water from shallow and deep wells. This source provides a more stable supply but it replenishes at a fraction of the rate that it is being used. Shallow wells have a 50-80% efficiency rate and they are becoming unreliable due to depletion. Deep wells have a 70-90% efficiency rate but, as you will see below, they come at a high costs—both economically and environmentally.

Neither of these sources are being managed sustainably. But at this point, “unsustainable” feels like an understatement—a word too soft for the reality of what’s happening. Groundwater isn’t just being overused; it’s being permanently crippled, like draining a retirement fund with no way to replenish it. And with that analogy, let me anthropomorphize how we are treating water right now. To us, it feels like water will never run out. It's just... there. How could it go away? It almost feels abstract. So I will paint a picture for you with something that you may not, ironically, take as for granted: money.

5.2. Contaminants

When it comes to irrigation, it's not just the quantity that we need to be concerned about. Crops especially require high-quality water as well. Unfortunately, not only are we overusing the resources but we are contributing to its contamination.

5.3. Is the Cup Half Empty or Half Full?

Freshwater is unquestionably the most valuable natural resource that we have. This isn't an exaggeration. We have oil & natural gas, arable land, forests & timber, and rare earth minerals. None of those resources, nothing—economically, agriculturally, or biologically—functions without freshwater.

Ogallala Di Da

During the American Revolution our soldiers used an Uno Reverse card with the song Yankee Doodle. In similar fashion, most living in the middle of the country have taken the term 'flyover states' and use it as a badge of pride. Much of this area is also known as the Heartland. If anything deserves to be considered the proverbial heart of the United States, it's difficult to contend with the Ogallala Aquifer.

The Ogallala Aquifer formed 12,000 years ago from melting glaciers. is the largest freshwater source we have, spanning 175,000 square miles beneath the Great Plains, with a depth being 1,000 feet at its deepest point. If you've never heard of this source, that's understandable. Nearly all of it is at least 100 feet underground. I encourage you to check out other information sources for how extraordinary this aquifer is for us and you can learn everything you'd like. I on the other hand am going to share with you a bit of information that you probably won't like so much (actually, you shouldn't).

There was an expansion of groundwater pumping in the 1940s-1950s that was driven by fossil fuel-powered pumps. Reports have shown places where the water level of the Ogallala has already fallen 100 to 200 feet. The Ogallala recharges itself at ~1 inch per year. We use so much water from it that only 10% of what we extra is replenished annually. Yes, we use 10x as much water as it is capable of replacing itself.

It supplies over 80% of the region's drinking water. More than 90% of the groundwater pumped from the aquifer is used for irrigation. It alone is utilized for 60% of irrigation from groundwater and provides nearly one-third of total irrigation, making it the single most important water source we have. And it has already been confirmed unrecoverable in some areas.

Floridan in Flux

So we just move to the next largest water source, right? Fortunately, the best news we have about the Floridan Aquifer is that it has a high replenish rate. In areas where it is unconfined or semi-confined, it can recharge approximately 10-25 inches per year. That's at least better than the ole slowpoke of the Ogallala.

Here's the issue. The Floridan Aquifer flows throughout a type of landscape that's called karst. Limestone. Overextraction in various regions causes large areas of land to begin to gradually lower. That's called subsidence. That takes awhile to happen so you probably aren't as familiar with it as you are with it's much quicker-to-appear sister, sinkholes.

Some studies claim success—that we're not over-extracting the aquifer—but they're a bit misleading which is caused from the higher replenish rate. It is like if I pull a rug out from under you and place it back down quickly, I can claim to everyone else that the rug is still in the same place so there's no way you're hurt. While half true, people who didn't see it and only listen to me move on with their day. Meanwhile you're trying to pick yourself back up with hardly anyone's help. I'm sure the Ph. D's and corporate studies will unironically dissipate from being cited while regions begin to quite literally collapse. (Un)fun fact: Sinkholes and subsidence aren't even the most frequent or severe concern we have. It is just the second-largest issue we have with the Floridan Aquifer.

The most prevalent issue: nutrient pollution. This issue is shared with the Mississippi River Valley Alluvial Aquifer. This aquifer has 90% of its extracted water being used for irrigation. But as easily accessible surface-level and groundwater sources become more unreliable, deeper wells are dug. While the Floridan Aquifer is the 2nd largest behind the Ogallala, The Mississippi River Valley Alluvial Aquifer sits atop the Mississippi Embayment Aquifer, which is also our 3rd largest underground water source.

Mississippi, maybe?

While the Mississippi Embayment is #3 on the list of size, it comes in as our #2 most used groundwater source. The Floridan Aquifer has almost 4 billion gallons of water withdrawn per day. The Mississippi Embayment loses about 11 billion gallons of water each day. The Ogallala Aquifer: 17.5 billion is extracted. Yes. Those are billions with a B. And that is each day.

Water doesn't sit alone as the only resource that is over-extracted though. The land that is farmed on is just as overused—except worst than the soil erosion that is also an issue (yes, there's many more issues than listed in this article)—the consistent farming of land causes nutrient pollution. This is where what we essentially farm the land so much that the nutrients from the soil begin to deplete faster than they can replenish (hm, recurring theme, huh?). This happens quickly enough that each year farmers need to lay chemicals such as nitrogen and phosphorous across the soil so that there will be enough for the crops to actually have the nutrients they need to grow.

Since the soil's nutrients have been depleted, farmers can't lay "just enough" down because unfortunately, not all of it is able to make its way to the crops. The excess of chemical flows and finds its way into our water sources. Given the name, I'm sure you can guess where the groundwater extracted from the Mississippi aquifers and irrigated onto the fields eventually find the water carrying these contaminants—the Mississippi River. The river basin that produces over 90% over our nation's agricultural exports and nearly 80% of the entire world's exports in feed grains and soybeans.

Say it ain't Salt

There are times when there is drought, low rain and snowfall, and now increasing nutrient pollution, where our surface water sources such as the Mississippi and Colorado Rivers aren't capable of providing what is needed to irrigate. When this happens, farms often turn to the shallow wells to use underground sources. As these shallow wells become unreliable, deeper wells are drilled into confined aquifers, such as the Mississippi Embayment and Floridan Aquifer. And this is where we have the most concerning issue based on severity.

It's salt.

Salt prevents plants from absorbing water through osmosis, leading to dehydration and crop failure. At best, salinity buildup reduces permeability (essentially how easily water and nutrients move through soil to reach plants) which cuts yields by 10-15%. At worst, if soil becomes too salty, crops die. Sounds bad doesn't it? Well, that's not the worst part.

A major concern with deep well extraction is saltwater intrusion. This is where excessive pumping from groundwater sources allow ways for saltwater to enter into an aquifer. Unlike seawater, which is a continuous and replenishing body, an aquifer functions as a storage tank—once it’s contaminated with salt, it does not easily flush out. Surely it's not as bad as it seems though. We would just now have some dead crops and our new fancy desalinization technology can be used to give us our quality water back, right?

Wrong. While salt infiltration into the soil may render the farmland unproductive for years or decades, which has a very high cost to remedy in and of itself. The same can't be said for our aquifers. Excessive pumping reduces freshwater pressure, allowing saltwater from the ocean to seep into the underground reservoirs. And that's where it contrasts and is the worst part. There is a difference between manageable damage and irreversible events. Saltwater intrusion into our groundwater sources permanently contaminates freshwater, rendering them unusable forever.

The Floridan Aquifer and Mississippi aquifers, and others closest to the coast, are much more susceptible to these severities. For aquifers such as the Ogallala, you would think with it in the middle of our continent, it would be safe from salt or seawater. Yet overextraction changes geological formations that will pull up deeper, saltier water, increasing groundwater salinity over time.

Even if no additional deep wells were ever drilled starting today and water extraction completely stopped from them moving forward, the land subsidence and infrastructure that degrades will create new pathways for salinization over time. Multiple ticking time bombs have been started. We've put into motion inevitable, disastrous ecological feedback loops. More and more is being taken from less and less. If you're on a plane and the pilots start removing the windows so more people have access to airflow, you may question that. During descent if you then see them out dismantling the wings to cut off dead weight and get to the destination faster, you may think of this article and realize taking more and more from less and less doesn't end so smoothly. Surely somebody will step in, up, or out for us to do... I don't know. Something!

5.4. Failed Leadership: The Illusion of Solutions

This is when we need leadership the most. Or empathy at the very least. Instead of tackling the root issue—overuse—governments continue to push expensive, logistically flawed infrastructure projects to shift water away from one region to another. These plans do nothing to reduce demand. They simply redistribute scarcity. It's one thing to spread risk. It's a completely different thing to say, "well at least I got mine."

The Central Arizona Project

The Colorado River Compact (1922) divided the river's water between seven U.S. states and Mexico. There were then large-scale projects such as the Hoover Dam (1936) and Glen Canyon Dam (1963) that diverted massive amounts of water before the water even reached Arizona. In the early 1990's, one of the largest water infrastructure projects was completed after 20 years of construction that cost $4 billion. A 336-mile canal system diverts a significant portion of the Colorado River's flow to supply Phoenix, Tucson, and surrounding agricultural areas in Arizona. Add persistent droughts in the Southwest. The once lush, thriving ecosystem Delta in Mexico—the Colorado River no longer makes it to the ocean.

I have to give credit where credit is due. CAP's commitment to transparency, education, and governance with public representation is commendable. The debt repayment will continue for another 20 years. They've experienced unexpected energy costs spike and the continued dwindling Colorado River with reduced supplies, not to mention the ongoing maintenance. Farmers who utilize approximately 30% receive special subsidies, though those are now on the chopping block. While Arizona has been one of my favorite states to visit in the country, I don't live there. Maybe a resident could ask a local farmer how they will manage the upcoming decreased water supply with simultaneous increase in costs for that water. I anticipate we won't be seeing an increase in the number of small family-farms for Arizona.

Missouri River Aqueduct Proposal

If anyone has any free history books, I encourage you to send them to: 1773 N Road B, Ulysses, Kansas, 67880. The Kansas Aqueduct Coalition is currently leading the repeated advocacy for the Missouri River Aqueduct Proposal. Estimated at $20-30 billion dollars, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers initially proposed and envisioned this 375-mile canal to transport water from Northeast to Southwest Kansas. I guess since Kansas shares a border with Missouri where they have access to a whopping 75 miles of the nearly 2,500-mile river, they have plenty of reason to disregard the overwhelming negative economic and environmental impacts. For the rest of the people downstream, "At least I got mine."

Other (not so) Thoughtful Solutions

Is it understandable that our leaders have not come up with better solutions? Since the signing of the Declaration of Independence to now, the U.S. population has experienced 100x growth. As cities became meccas and the Industrial Revolution improved productivity, increased rate of water usage has grown significantly. Have there been enough problems, or very much time, for leaders to actually consider the different issues and possible solutions?

The first time anyone even mentioned early signs of any sort of water crisis was... oh... a mere 130 years ago. Okay, that may have been quite some time. Though in the grand scheme, it's been a century since the Dust Bowl. So, why worry? There was the prolonged drought in the Northeast and it's been 60 years since then. Environmental damages haven't begun being taken somewhat seriously until the past 50 years. There was The Farm Crisis of the 1980's. Wait, we had a farm crisis in the 80's? We did, but it's barely been 30 years since the escalating concerns of aging infrastructure. The downplaying of the severity of the public health disaster from the Flint, Michigan water crisis was hardly even 10 years ago.

Oh. Okay, I get it. It's been so long ago since we have even had any issues... Or, wait. No. There just hasn't been much time to plan... or, wait a minute...

This is maybe the part in the writeup where you thought you were reading a research article and are wondering why it's starting to sound like a cynical op-ed. Well, frankly. It's because I'm infuriated. And you should be too.

If you are in any role or leadership position reading this and right now you are thinking, "Oh come on... Look at all we've done!"

You haven't. done. enough.

Some policies implemented include water usage measurements. These measurement are self-reported. Clearly those with integrity will provide as accurate information as they can, while those who use and abuse have no check in place. It's nearly all calculated with practically napkin math. Flow meters for irrigation pumps are equipment that record the velocity of water coming from a pump and it calculates an estimated gallons per hour. They are expensive at best. At worst, due to their design and measurement methodologies, they are often inaccurate and unreliable. They are highly temperamental, demanding constant adjustments and repairs. Instead of functioning as intended, they waste a farmer's time—diverting efforts to fixing a minor component when attention is needed elsewhere.

If you've ever talked to an overworked, stressed out farmer whose running on 2 hours of sleep and by a field when it's 105 degrees out and they need to be driving a sprayer but they're stuck trying to fix a "(explicit words) piece of (explicit words)", well then you have some understanding. It's why they wish those who made decisions that affected them and built things for them would may consider visiting a farm to see what it's like in-the-day-of-a-life. On one hand there have been funding programs that will cover expenses for this sort of equipment, where there are success cases. More often there are added burdens and operational costs—farmers ditch them after. On the other hand, there have been regulations demanding farmers to cut groundwater use by 10-15%. This is even with the known measurement issues. These are the best solutions?

Another fallback policy besides limiting water usage is introducing water allocations. I'm almost exhausted at this point of the ineptitude. So, just Google the term and you will immediately see how infighting and corruption has caused this tool to be hardly effective.

I'll conclude that THE most failed leadership illusion of solution has been the idea that, "We don't have a water supply problem. We just have a distribution problem." That thinking has repeatedly, time and time again, led to solutions that just pass the problems off to someone else.

We need better leadership.

5.5. PumpTrakr & Conservation Tech

Why irrigation technology is hard and conservation adoption has been slow

Soil Moisture Sensors

Automated Irrigation - PumpTrakr

5.6. If We Keep Business as Usual

The growing (un)incentives to change

Water policies are based on outdated climate assumptions

The overuse feedback loop to collapse

---

Every issue we've discussed—labor shortages and land ownership, investments and regulations, imports and exports and conservation efforts—each has been a system humans have created, controlled, and mostly tried predicting.

Here is the truth very few have accepted or even believe: once you look up from what is happening right now in each of those systems, the certainty of predictability ends. I'm going to repeat that for emphasis: the certainty of predictability ends. As odd as it may seem, putting a percentage on ANY (un)likely event is simply irrational reasoning. Yet it's done—even by the best experts in all of these domains. And since all of these systems are so intertwined and interdependent, I will share with you how our entire society has been making decisions from sets of numbers that are stacked one after another and we've built multiple houses of cards.

Few seem to accept the answer of, "We don't know." And fewer seem to care.

6. Systemic Risk & Black Swan Exposure

7. Counterarguments & Alternative Perspectives

Conclusion

Previous Change Log

(This article is a work in progress. Below is a record of updates and revisions.)

February 8, 2025

Section 5: Expanded on Section 5. And minor grammatical edits in other sections.

---

February 7, 2025

Section 5: Began releasing Section 5.

Added URGENT note: Last week I posted an article within 12 hours of the administration's freeze on federal grants and loans. If you followed the news you know there was mass confusion. I took it down less than 2 hours after posting as a supposed clarification came out and it seemed the ramifications were not going to be as widespread as I had assumed.

I've recently come across stories that some of my assumptions were in fact correct, which includes the massive ripple effects this is going to have on our economy (ESPECIALLY FARMERS AND RURAL COMMUNITIES). Here is the post with a letter and links for you to easily contact your Congressmen and women.

---

February 6, 2025

Intro/Outro and Outline of Section 5: Let this be a lesson in investigative/research journalism: don't promise a one-day turnaround. After additional research, brainstorming, writing, editing, and a couple days worth of conversations with AI, clarity for the purpose of this section became clear. I initially planned to share the various small and medium-sized issues that I've experienced adding up. I've realized this section needs to go deep rather than broad though, and be incredibly insightful rather than light touch. The truth is that every word is intentional, serves a purpose, and is necessary because of the gravity of the situation. This one has been tough to write, as a process itself just to get through, but even more so on a personal level because of just how real these dire situations are. I'm just writing words. There is an immediate need though that demands more action.

---

February 4, 2025

Release of Section 4: First draft of section "4. Geopolitical & Global Market Considerations".

Editing: Added a few infographics to the Initial release sections. Added about 600 words to the Initial release sections. After further research today, there is some additional critical information I will be coming back to add to the first four sections after I complete the remaining sections. More imagery will soon follow for your visual pleasure. Stay tuned.

---

February 3, 2025

Initial release: First drafts of sections "Introduction", "1. Labor and Market Demographic Realities", "2. Domestic Economy and Policy Pressures", and "3. Industry Collapses & Historical Parallels"