Questioning Rural: An experience of regional startup and tech-based economies for small communities (Part 2 of N)

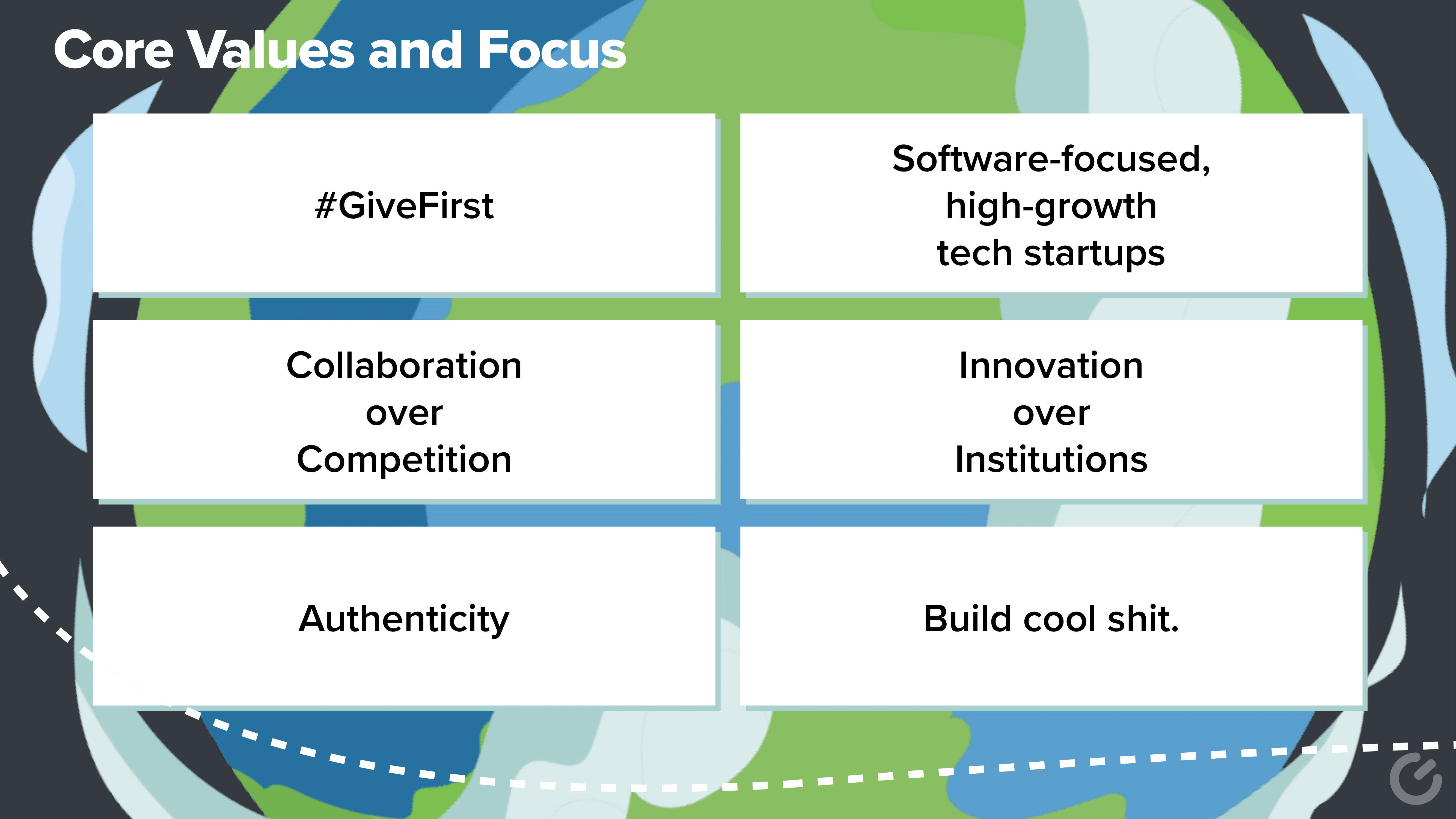

Six principles for how we guide our work

If this is your first reading, I would recommend starting at Part 11 as this is a series that is cumulative from a presentation given.

(~18 minute read)

This is subjective. It’s personal. But it’s foundational and rooted from real experiences. There is no question that setting these as Core Values and Focus were some of the main contributors for progress.

What if the number one currency when it comes to startup and tech-based economies, is not in fact the U.S. dollar? (No, not Bitcoin either). Someone doesn’t have to be around this work long at all to hear the often quoted, “Less than 1% of all venture capital goes to rural startups.”

When I hear most people talk about this statistic they are painting the picture of the lack of accessibility for small towns and rural communities, with an emboldened mission that we need to solve for the inequity. While maybe well-intentioned, I feel like there has been a missed opportunity with the message that’s taken from it.

I wonder what it looks like if that statistic is used as our battle cry, the chip on our shoulder, as underdogs. I would like to take out the defeatism from saying, “we’re less fortunate and are held back” and instead say, “look how much we can do with so little”. What does it look like with that paradigm shift in thinking and how we share our stories? Of course, that comes with the cynical afterthought of questioning how something is supposed to be done with nothing, or that it must be so nice to even say that at all.

I’m not saying we don’t need capital. I’m asking if we are more effective when more of our focus and attention is changed to a currency that could be the most fundamental method of increasing our velocity for progress. Trust.

#GiveFirst

I have to admit that I learned about #GiveFirst from Startup Grind2 and it originally came from Brad Feld3. So credit for the phrase has to go to them.

Trust is one of the most powerful tools to lower transaction costs when it comes to building startups, tech companies, and working on regional startup and tech-based economies in small communities. Every interaction and introduction, connection at meetings or events, phone call and email, and financial and working relationship includes transactions that have a cost associated with them. That cost could be time, money, reputation, opportunity, risk, etc. Maybe someone much smarter than me can provide scientific or mathematical proof for this: what if using trust to lower transaction costs overall takes less of an investment while at the same time has a greater return than any other currency we can use?

With viewing trust as currency, the speed of spending that currency becomes a main driver for progress, and it shows our intentions with transparency. In Did the Lean Startup Cause a Fat Problem4, I talk about speed as the rate at which we learn and create new things and connections, not the rate at which we optimize. Optimization is focused more on the known which has benchmarks, whereas learning and creating can be focused on the unknown which is potentially boundless.

(Note: I have more to share on this but it becomes less palpable within this specific medium. So if you enjoy the abstract thought, check out The Rainforest5 by Victor Hwang and Greg Horowitt starting on page 52 of the book that has diagrams explaining nodes and connections in imaginary worlds versus what’s reality. When you broaden the context to small regional communities working on startup and tech-based economies the systems break down even further.) Let’s get back to being more practical.

When we come to the table, we come with a level of trust that we believe everything that is said is true, there is expertise or experience, and there are good intentions. Especially when we begin to decide that we could work together, the first thing on our mind is not, “what’s in this for me?” Of course we need mutually beneficial relationships, but in nearly all cases, we don’t start a relationship trying to gain something. We start by thinking how we can give to that individual, program, company, organization, community, and industry in ways that will help with whatever they may need or however we can. Payment or repayment may come in the future. It may not. It may be to us. It may be paying it forward to another founder. It may be to benefit our region that we may never even know about.

When we start, we always look to give first. In your next meeting, I encourage you to think of something you can do or give with no intentions of getting something in return. *Let me asterisk this with that it must be handled with care. It must be done from a genuine place that is authentic (more on that later).

Software-focused, high-growth tech startups

Frankly, we use this as a guiding principle because it narrowly defines what interests us most. #GiveFirst can be never-ending, thankless, and sometimes you’ll never see reward from it, so with that in mind, then we at least get to work in areas we enjoy.

Part 3 of this series will describe in much more detail the deeper rationales for why we focus on these specific areas. While most of these guiding principles are subjective or warm and fuzzy, there are also theoretical, mathematical, and scientific findings that explain why these specific things are so critical to progress within small towns and rural communities–at least if they want to be a part of the economy in the future.

For me personally, software and startups spoke to some core purposes of life.6 With software, someone can create almost anything that comes to mind. With startups and entrepreneurship, it’s the same. Pursuit can be determined by interest or hobbies, pure curiosity, problems, or opportunities. Combine startups and tech and there are near limitless possibilities to create lives, communities, societies, worlds, and realities. Whether it’s unhappiness from where we’ve come from, how things are now, or what the future may look like, this knowledge can be used to create change in nearly every aspect of life. When you have tools at your disposal with this sort of potential, you can create opportunities for economic mobility and a higher quality of life for yourself, your family, and many others.

I’ve worked on launching my own tech startup, enjoyed getting my hands dirty working to help other founders start and grow their own, been a coach and mentor with less of a focus on telling people what I think they should do and more helping them ask focused questions, and been fortunate to bring a variety of resources to communities to help hundreds of founders. But the joy has been much less about I, me, my, and mostly stems from the shared work with others. Which leads to…

Collaboration over Competition

(~12 minutes remaining)

I grew up in Sikeston, Missouri which was a small town of less than 15,000 people. So when I heard or thought of Cape Girardeau 30 miles north, with double our population, I viewed it as a big city that had it all figured out. It seemed like everything there was better than what we had: people were smarter, richer, and society existed in this utopia and equilibrium where everyone had everything they wanted and needed …how naive I was.

The root of this came from early childhood years of competition. My obsession with soccer and baseball, with the underdog mentality, led me to believe that those we competed against wanted more than to just beat us in that game. I thought they viewed us as inferior and incapable altogether. And we sort of were. We mostly didn’t have the same access as them with infrastructure, both physical and societal, opportunities, and world views. So we played with what was given. We worked with what we had.

The more I’ve worked in my career, the more I’ve realized that there is always an old guard in town who have financial and social influence to control the direction of people’s thinking and actions. This is one thing small towns and rural communities have in common with metropolitans. But if you consider population and density, it seems that the smaller the population and lower the density, the more likely it is for a smaller number of people or things to have control and influence over everything.

Trust me. I understand. It’s easy to just say, “collaboration is key”. The reality is it’s often fruitless where we live. So, how is it even done? Well, to do things, we don’t wait for “blessings” or permission or go around kissing all the rings from groups who focus on keeping their share of the pie. Some people call this small-town thinking–that new and different means losing and taking away. In reality, their silos and barriers make it more difficult for people to work together. How can we make the pie bigger for everyone?

While new things can mean old things go away, emergence creates more than it destroys. The horse carriage drivers may have complained of losing jobs when automobiles became more prevalent, but the number of new jobs and quality of life created around a tool that increased our capabilities to travel farther and faster significantly exceeds what we had previously. We can argue that the automobile industry caused more net problems with examples such as Detroit or pollution, but most historical problems created are symptoms of a root cause which was not planning effectively or adjusting to change–thinking about competing and staying the same rather than working together to make progress.

Historically, competition has driven innovation, but it has also led to isolation and fragmentation, particularly in smaller communities. “Collaboration over competition is about building a sustainable future where no community is left behind” is a sentence that either makes someone feel good about accessibility and progress or feel bad with concerns of losing identity, depending on how they read it. The positive way of reading it expresses that everyone benefits. The negative way is that everything is diluted and identity could be lost. It’s important to understand that fact when considering where collaborations will be receptive versus rejected.

Without going down a philosophical rabbit hole, in the grand scheme of things, the words collaboration and competition are subjective. Depending on our lived experiences, different people can view the exact same situation and come to oppositive conclusions that it was collaborative or not collaborative and competitive or not competitive. Practically speaking, we collaborate where we can find common ground, and that is easier to define when we #GiveFirst. We know when to stop when it becomes clear we’re being taken advantage of, and it’s most important to quickly cut away from bad actors.

In The Beginning of Infinity7, David Deutsch addresses bad actors in the context of his broader discussions about the nature of knowledge, progress, and problem-solving in society. He argues that problems are inevitable in any society but that they can be solved given the right knowledge and conditions for the creation of that knowledge. When it comes to bad actors—individuals or groups who act destructively or unethically—he suggests that a society's resilience and ability to continue making progress depends on its institutions and their ability to foster cooperation and deter detrimental behaviors.

Deutsch emphasizes the importance of designing social, political, and legal systems in ways that minimize the harm that bad actors can cause while maximizing the potential for creative and beneficial solutions to emerge. This aligns with his overarching philosophy that with the right knowledge and conditions, societies can make unlimited progress. So how do we work with those institutions?

Innovation over Institutions

This is the point where I may offend a lot of the people who are in this area of work. Small towns and rural communities have had decades of declining trends in population, wages, opportunities, and quality of life. That says to me that the leadership and institutions that have been in place of power and influence have failed us. That feels harsh, but the language is intentional.

In my younger years, I viewed things more black and white where it seemed like every day was another revolution, but I’m not suggesting we go all neo-anarchism with a decentralized anti-hierarchy as a response to pervasive and inescapable corporate, government, or fundamental coercion. Institutions in and of themselves are not necessarily flawed, but when it comes to startup and tech-based economies in small towns and rural communities, we often can’t rely on them–especially in the sense of traditional economic frameworks that are used for larger, established regions and metropolitans.

Two examples.

We have “less than 1% of all venture capital goes to rural startups” and also “80% of venture investment goes to California and New York.” The response to that has been to lambast venture capitalists for inequitable distribution of investment. But can we really blame them? It makes much more sense for institutional capital to focus in metros where there is the highest degree of connectivity and it is most efficient to deploy funds that are very high-risk. Why increase costs for lower returns? If the odds of a startup founded by an Ivy League graduate in Palo Alto growing to a unicorn is extremely low, we can surely understand why it hasn’t made the most financial sense to focus on small towns.

To be clear, I’m not saying venture capitalists are unnecessary. I’m questioning if it’s a flawed idea to consider it a core part of our economic growth model in small communities. Surely there are better, more relative ways to manufacture opportunities that help people create high-growth tech companies.

Some studies indicate that a research university is a key ingredient to a startup and tech-based economy (I’d argue it’s the other way around, but I’ll save that thought for another day). This is one of the reasons why the idea that universities must play a part in economic development has flourished. Top universities have entire departments dedicated to entrepreneurship and small business outreach.

In smaller communities, historically what has emerged has been extensions. These were from a time when the expertise was expected to be housed in a major research institution and “extended” to other regions as opposed to encouraging as much innovation from locals. Sometimes organizations think we need university involvement in order to succeed. But it’s simply not true.

Again, to be completely clear, I’m not saying universities and colleges are not important. I’m questioning the level of importance and responsibility put on them where some people think starting, building, and growing startups and/or startup and tech-based economies in a smaller communities is impossible without them. In my experience. It’s not.

We can continue this line of thinking to include other institutions: government, legal, media, large corporations, etc. We say innovation over institutions because institutions by design are slower to move. This isn’t a dig at their value to society or anyone that works within them. It’s how they’re meant to move. If we had Senate Scrum Masters and House of Representative Lean Coaches who ran two-week sprints to test new laws every month, society would probably be a little too chaotic to function.

For regional startup and tech-based economies, especially in smaller communities, we align our work with those who are more driven by innovation than those with an interest in protecting institutions. I highly recommend The Evolution of Everything8 by Matt Ridley. The overarching message resonates with this concept.

“Positive emergence overwhelmingly comes from bottom-up.”

- Matt Ridley, The Evolution of Everything

I’ll add a final thought here. This is also by no means an argument that institutions play no part in regional startup and tech-based economies. Unfortunately, when you look at traditional economic frameworks, hell even recent frameworks that have started to come out about startup ecosystems they are all the same where they say the major institutions must play a part. In reality, a lot of our communities don’t have access to all of them, sometimes any. I’m writing for those people. The ones who read books, watch webinars, go to conferences, hire consultants and you end up leaving with, “how am I supposed to help us get there without that?”

Authenticity

(<5 minutes remaining)

If we can’t face the facts to discuss difficult topics then we’re going to stay in neutral. Whether it is the person who says they will help with no intentions of actually doing so, the software that promises more than it delivers, the program that reports vanity metrics or moves goal posts that share outcomes to look better than it really is, the umbrella organization that takes more than it gives, or the community leadership that says we’ve been doing great when data shows subpar results or declining trends for years–the inauthenticity is abhorrent.

We want to be transparent and direct. There’s a difference between superiority complex and arrogance compared to candor. Radical candor. Ed Catmull discusses candor in Creativity, Inc9. as he shares the culture that was created at Pixar. How much more refreshing is it when we are honest, open, and straightforward without aiming for gotchas, being opaque, or dodgy?

This isn’t meant to say we go tell everyone who we think is wrong. It’s one thing to be nascent with inexperience. It’s another to be misinformed. It crosses the line when it’s blatantly disingenuous. Unfortunately, there can be a lot of the latter in startups, tech, and the organizations that help them. This isn’t specific to smaller communities, but the ramifications of it are more detrimental. Oftentimes there is one person, division, or organization that “owns” an entire area of work. Which means entire networks and systems can be linchpins.

Our main take is that we assume everyone comes from a place of good intentions; it’s okay to fail or be wrong–let’s discuss those things openly. But to be deceitful by distorting information or the narrative knowing it may harm others for personal gain is unacceptable. This is an area where institutions play critical roles because of their resources and influence. In my experience, the ones who are genuine are wind in the innovators sails. The ones who aren’t, can stagnant an entire community and region. So it takes authentic, candid conversations to address root causes of problems to work together to make meaningful progress.

What if we say what we feel and feel what we say? What if we do what we mean and mean what we do? It can feel raw. But everyone knows where we stand. And that allows us to work on some pretty cool shit.

Build cool shit.

Ironically, we didn’t set out to build startup and tech-based economies. We didn’t even set out to focus on economic development in general. We just wanted to work on intellectually stimulating projects with talented people. That meant helping people be innovative and building our own startups too. We ask, “what if everything we do, by design, is built like a high-growth tech startup?”

What this forces us to do is align our personal ambitions and purpose with our work. There’s this whole anti-work movement going on where people scoff at the idea that work and personal life don't need to be combined. There are some jobs where this is a bit harder than others without crossing the line of being just plain disingenuous. But when we give people direction and then the autonomy to create how they envision things should be, it’s pretty powerful.

At the same time, it means people will outgrow us. We’ve had multiple people in our organization go on to start their own companies. That’s a win for us. This isn’t easy. It can seem disorganized, inefficient, or plain insane some days. But we try not to put structure unless it’s absolutely necessary. On this note specifically, I will eventually share with you tools and frameworks I’ve used to help guide through this ambiguity.

In the future, I’ll also share some of the cool shit we’ve built. How we did it and why we did it. Which brings me to the conclusion of Part 2 of this series.

We’ve had more mantras, slogans, and values throughout the years. I felt like these were some of the best to share because they transcend levels. As individuals, we can take these concepts and run with them. If we’re starting a new program or effort, we can use these guiding principles. Even though I’ve mentioned the work that it takes to foster startup and tech-based economies is oftentimes in direct contradiction with the very companies and people it is trying to help, these principles can still be used in both settings: from startups to Entrepreneurship Support and Workforce Development Organizations–all the way up to community, region, and industry.

I don’t have all the answers. But I’m not going to stop asking questions. For me, this is us asking, “How?” Like I said, it’s also the subjective, warm and fuzzy part of what we do. In the next writeup, I’ll share the more concrete question of “Why?”

How do you guide your work?

The following footnotes are strictly for easy reference. I’m no affiliate marketer.

The Rainforest: The Secret to Building the Next Silicon Valley by Victor Hwang and Greg Horowitt

The Beginning of Infinity by David Deutsch

The Evolution of Everything by Matt Ridley

Creativity, Inc. by Ed Catmull

Chris - you continue to serve as such an important voice as we explore ways to responsibly grow the tech ecosystem in rural and small communities. Go. Just go! 🙌